-

Email us at:

info@weltreatsystems.com -

Call us on:

020 - 41228334 - Download Brochure

21

Jan 26Let’s get one thing straight at the start.

Modern water threats are not driven only by climate change. Droughts and floods grab attention, but the most dangerous damage to water systems happens quietly and continuously. The biggest driver behind this slow collapse is man-made pollution, especially industrial effluents.

This is not an emotional or activist argument. It’s a reality-based explanation of how water threats are being created, why industries play a central role, and why effluent treatment has become unavoidable if water security is to survive. The scale of this problem is planetary, yet its origins are often found in pipes, drains, and discharge points within industrial zones. Understanding this dynamic is the first step toward a viable solution.

Understanding Modern Water Threats (Beyond Climate Change)

Water threats today are far more complex than simple water scarcity. They include:

- Freshwater sources becoming unusable due to contamination

- Long-term groundwater pollution

- Ecological collapse of rivers and lakes

- Unsafe drinking water supplies

- Damage to agriculture and the food chain

The critical distinction most people miss is this: Water availability does not mean water usability.

In many regions, water still exists physically—in aquifers, rivers, and reservoirs—but pollution has rendered it unsafe or economically impossible to use. Consider a river that flows through an industrial belt: it may hold billions of liters, yet be biologically dead, unfit for drinking, irrigation, or recreation. This is not a natural failure of ecosystems. It is a failure of human systems, specifically our management of waste and our tolerance for externalizing environmental costs.

The narrative of water stress is often reduced to maps of declining rainfall or shrinking reservoirs. While real, this narrative obscures a parallel crisis: the degradation of water quality. A community can survive lower water volumes with careful management, but it cannot survive water poisoned with heavy metals, persistent organic pollutants, or toxic salts. This qualitative collapse, driven predominantly by industrial activity, represents a direct and pervasive threat to human health, food security, and economic stability.

How Industrial Growth Turned into a Water Threat

Industrial development brought economic growth, employment, and technological advancement. That part is not disputed. The problem began when waste management failed to evolve at the same pace as industrial output. The linear “take-make-discharge” model, a hallmark of 20th-century industry, treats water bodies as infinite sinks, capable of endlessly absorbing and diluting waste. This model is fundamentally broken.

Modern industrial effluents are:

- Chemically complex: Unlike primarily organic domestic sewage, industrial wastewater can contain thousands of synthetic compounds.

- Persistent in the environment: Many industrial chemicals do not break down easily; they bioaccumulate in living tissues and persist for decades.

- Difficult to dilute or neutralize naturally: Ecosystems have no evolutionary experience with many man-made compounds, rendering natural purification processes ineffective.

Industries such as textiles, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, food processing, leather tanning, and metal finishing discharge wastewater that is not just “dirty,” but chemically aggressive. These effluents are cocktails containing:

- Heavy metals (e.g., mercury, lead, chromium, cadmium) – toxic even at minute concentrations, causing neurological damage, organ failure, and cancer.

- Toxic salts and chlorides – which increase salinity, rendering soil infertile and water corrosive.

- Oils, greases, and solvents – creating films that block oxygen transfer, suffocating aquatic life.

- Synthetic dyes and pigments – often aromatic compounds resistant to degradation, blocking sunlight and disrupting photosynthesis.

- Non-biodegradable organic compounds and emerging contaminants like pharmaceuticals and endocrine disruptors.

When such effluents are discharged untreated or inadequately treated, the damage cascades. Surface water contamination is the first visible sign, but the more insidious threat is groundwater contamination. Pollutants seep through soil layers, eventually reaching aquifers—the primary source of drinking water for billions. This damage is often irreversible; cleaning a deep aquifer is technologically daunting and prohibitively expensive, if not impossible. An industry’s short-term cost-saving on effluent treatment can thus mortgage a region’s water security for generations.

Industrial Effluents: The Most Underestimated Water Threat

The most dangerous aspect of industrial effluent pollution is its invisibility.

Floods are visible. Droughts are visible. A river turning a startling color from dye discharge is visible. But the slow, steady poisoning of an aquifer is not. It is a silent, subsurface crisis.

By the time observable signs appear in communities, the damage is already deep and widespread:

- Borewell water develops an odd odor, taste, or discoloration.

- Laboratory tests reveal Total Dissolved Solids (TDS), heavy metals, or nitrate levels exceeding safe limits by orders of magnitude.

- Crop yields decline inexplicably; soils become saline and crusted.

- Long-term public health issues—elevated rates of cancers, kidney disease, developmental disorders—increase in clusters around industrial zones.

In many cases, by the time the problem is acknowledged, aquifers have reached a point of no return, where natural recovery is impossible within any human timeframe. This combination of potency, persistence, and invisibility makes industrial effluents one of the most underestimated—and therefore politically neglected—water threats today. The cost of inaction is deferred, but it compounds dramatically.

Why Water Threats Are No Longer Local Issues

There was a time when pollution was considered a “local problem,” contained within a factory fence or a nearby river stretch. That assumption is dangerously obsolete. Water systems are the original network, indifferent to human-drawn borders.

The reality of hydrological interconnectedness means:

- Rivers are linear conveyor belts of pollution, carrying contaminants hundreds of kilometers downstream, across districts and states.

- Groundwater aquifers are vast, slow-moving underground reservoirs that do not follow administrative boundaries.

- Polluted water enters agriculture and the food supply, meaning toxins can travel from an industrial discharge point onto dinner plates in distant cities.

As a result, the consequences are systemic:

- One poorly regulated industrial cluster can compromise the water security of an entire region, affecting millions who have no connection to the industry.

- The health and economic costs—from medical bills to lost agricultural productivity—are borne by society at large, not just the polluter.

- Water threats today directly impact national supply chains, public health budgets, and regional social stability, transcending the realm of “environmental issues” to become core governance and economic challenges.

Climate Change Is a Stress Multiplier, Not the Root Cause

To be clear: climate change undeniably intensifies water-related challenges. It reduces river flows, alters rainfall patterns (leading to more intense droughts and floods), and increases evaporation rates. All this weakens the natural dilution capacity of water bodies.

However, intellectual clarity is crucial here. We must be precise:

- Climate change amplifies water stress (a quantitative problem).

- Industrial pollution creates water toxicity (a qualitative problem).

The interaction is lethal. Lower water flows mean that the same volume of untreated effluent results in higher concentrations of pollutants. A drought can turn a lightly polluted stream into a toxic canal. Conversely, floods can spread contaminated sludge over vast agricultural and residential areas. In this sense, climate change acts as a threat multiplier, making the existing problem of industrial pollution exponentially more dangerous.

But it does not create the pollution itself. The toxins originate from human industry, not a changing climate. If effluents were properly treated to safe standards, the stress imposed by climate variability would be significantly more manageable. Communities could focus on conserving and allocating clean water, rather than battling both scarcity and poisoning simultaneously.

Effluent Treatment as a Direct Response to Water Threats

Effluent treatment is often viewed through a narrow, compliance-driven lens: a box to be ticked to avoid a fine, a necessary evil to meet regulatory minimums. This perspective is not just outdated; it is a strategic blindness.

In reality, modern effluent treatment represents a frontline defense against man-made water threats. It is a direct intervention at the source of the problem. Proper treatment:

- Removes or neutralizes harmful pollutants, preventing them from entering and damaging the hydrological cycle.

- Enables safe reuse of treated water within industrial processes (cooling, washing, boiler feed), creating a circular water economy.

- Radically reduces pressure on freshwater sources by closing the water loop within industrial operations.

- Protects groundwater from long-term, irreversible contamination, safeguarding a community’s most vital reserve.

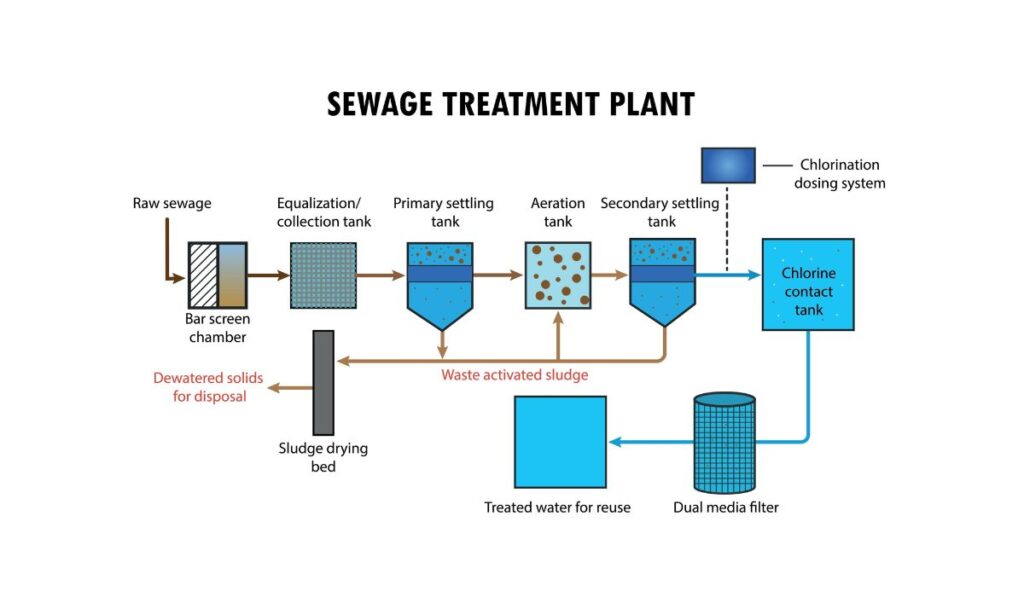

Simply put: Effluent treatment addresses modern water threats at their origin. It is not experimental or futuristic technology. Robust, proven treatment systems—from primary settling and biological treatment to advanced oxidation and reverse osmosis—already exist. The science is settled. The real challenges are not technical; they lie in mindset, execution, economic prioritization, and enforcement accountability.

Why Treating Industrial Effluents Is More Effective Than Finding New Water Sources

Confronted with water stress, the instinctive reaction of many industries and municipalities is to search for new water sources: drilling deeper borewells, purchasing water from tankers, or advocating for costly, energy-intensive long-distance water transfers like canals or pipelines.

These are classic supply-side solutions. They are inherently short-term, as they increase demand on already stressed sources. Their costs rise predictably, and they carry increasing regulatory and social risk (e.g., conflicts over water rights).

Effluent treatment and reuse offer a fundamentally different, demand-side approach:

- An industrial plant can use, treat, and reuse the same water molecule multiple times.

- We dramatically reduce dependence on external, volatile freshwater sources.

- Operational continuity strengthens, as municipal water cuts or droughts make the industry less vulnerable.

From a water-risk perspective, the equation is clear: Reuse reduces vulnerability. Discharge increases it. Investing in treatment infrastructure is an investment in water independence and long-term operational resilience. It transforms wastewater from a costly liability into a reliable, on-site resource.

The Mounting Cost of Ignoring Industrial Effluents

Delaying or neglecting effluent treatment does not eliminate costs. It merely postpones them and transfers them elsewhere—to society, to future generations, and eventually back to the industry itself in magnified form.

The long-term consequences of inaction are a cascade of failures:

- Regulatory & Operational: Increasingly stringent environmental laws lead to heavy penalties, production caps, or complete plant shutdowns. The cost of retrofitting treatment under regulatory duress is always higher than proactive investment.

- Legal & Liability: Industries can be held liable for environmental damage and public health impacts, leading to protracted lawsuits and massive remediation costs (e.g., Superfund sites in the US).

- Social & Reputational: Community opposition grows, leading to loss of social license to operate, protests, and damage to brand reputation that scares away investors, partners, and customers. In the age of ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) investing, poor water stewardship is a major financial red flag.

- Economic: Production suffers directly when water supplies are cut off or become too polluted to use. Regions with notorious water pollution struggle to attract any new business.

The most profound loss, however, is control. When an industry’s water sources become unreliable or unsafe, long-term planning and growth become impossible. The business is perpetually in crisis-management mode, reacting to the next water shortage or pollution scandal.

From Water Consumption to Water Stewardship

The paradigm must shift. Industries can no longer afford to ask only: “How much water do we need?” This question leads down the path of endless extraction.

The essential, survival-oriented question for the 21st century is: “How much water do we return safely to the cycle, and how can we reuse what we have?”

This shift represents a move from mere water consumption to genuine water stewardship. It means:

- Viewing effluent not as “waste” to be disposed of, but as a liability stream that must be managed and neutralized.

- Treating wastewater treatment infrastructure not as a cost center, but as core risk management and resource security infrastructure.

- Going beyond minimum compliance to embrace standards that protect the local water basin and community health, recognizing that a healthy operating environment is a prerequisite for long-term profitability.

Organizations that adopt this stewardship model are not just “being green.” They are future-proofing their operations, building resilience, and aligning themselves with the inevitable trajectory of global regulation and societal expectation.

Water Threats Are a Result of Choices

This is the fundamental truth. Natural disasters may be unavoidable acts of nature. Industrial water pollution is not. It is the direct result of human choices:

- The choice to treat effluents or to bypass the treatment plant.

- The choice to maintain treatment systems properly or to let them decay.

- The choice to invest in cleaner production processes or to stick with polluting ones.

- The choice, for regulators and policymakers, to enforce laws rigorously or to turn a blind eye for short-term economic gain.

- The choice, for consumers and investors, to support companies with responsible practices or to prioritize cost above all else.

Humans create modern water threats precisely because the solutions exist but they often deprioritize, undervalue, or ignore them in favor of perceived short-term advantages. The pollution in our rivers and aquifers is the physical manifestation of these accumulated choices.

Conclusion: Control What You Can – Industrial Effluents

No single industry, government, or community can solve the global water crisis alone. The challenge of Industrial Effluents is monumental and systemic. But in the face of this complexity, one fact offers a clear path forward:

- We cannot control the climate.

- We cannot command the rain to fall.

- But we can absolutely control how we treat industrial effluents.

Industrial wastewater is a major, proven driver of modern water threats. Conversely, effective effluent treatment remains one of the most practical, scalable, and immediately actionable responses available to us. It is a lever of control within our grasp.

The choice for industry, and for society that empowers it through policy and purchase, is straightforward:

- Path A: Allow industrial pollution to continue, letting it become a diffuse, irreversible, and exponentially costly downstream problem that pouses water security for all.

- Path B: Control it decisively at the source, transforming a threat into an opportunity for resilience, innovation, and sustainable growth.

The future of water security—for ecosystems, for communities, and for industry itself—depends overwhelmingly on which of these two paths we choose to take today. The tools are ready. The need is undeniable. The only question is one of will.